Finite State Machine in Typescript: Tiny Machine

A simple implementation of a finite state machine highly inspired in the XState library

Ricardo Sala

20 oct 2025

Any time that I wanted to build a component with a complex state - and by complex I mean with a lot of interactions among different pieces of state, conditions to transitions or side effects that should happen during those transitions - I ended up with the logic that manage that “machine” (even if not explicit, most of times it’s a state machine) all over the place.

After researching a bit about how others faced similar scenarios, I came out with the concept of finite state machines and the Xstate library.

Xstate seemed like a highly sophisticated library, and the learning curve was steep, and probably 95% of the complexity was not required for my needs, so I decided to create a very simplified version of it, hence tiny-machine library was born.

The library is highly inspired in xstate, and that’s intentional: I wanted the creation of this library to be both, useful for my apps and also a learning process to know more about how xstate worked under the hood. Again: it’s a very simplified version of xstate, far from the fantastic job done by the folks at Stately, so that I could easily switch to xstate if I ever had the need.

Architecture

Tiny machine has two main components:

Actor: Runs the machine logic and manages runtime state

StateMachine: Defines the machine configuration and transition logic.

That way, we keep the state machine pure, free from side effects (although its configuration defines the side effects, it does not run them), while the actor handles all the impure stuff (side effects, notifications, action execution). The machine is pure, deterministic and testable, while the actor manages its relationship with the world.

The Actor

Let’s take a look to the Actor interface:

export interface ActorRef<TContext, TEvent extends EventObject> {

id: string;

send: (event: TEvent) => void; // 👈🏻 Here is where the interesting stuff happens!

// Observable methods

getSnapshot: () => Snapshot<TContext, StateValue>;

subscribe: (

callback: (snapshot: Snapshot<TContext, StateValue>) => void

) => () => void;

//Lifecycle methods

start: () => void;

stop: () => void;

// Helpers

matches: (stateValue: StateValue) => boolean;

can: (event: TEvent) => boolean;

}As you can see, there is nothing complex going on there: just some methods to start and stop the actor, and others that allow external subscribers to be notified about the changes in the actor. And when I say “actor”, we could say “machine”, since our actor - as it is today - is only able to run state machines.

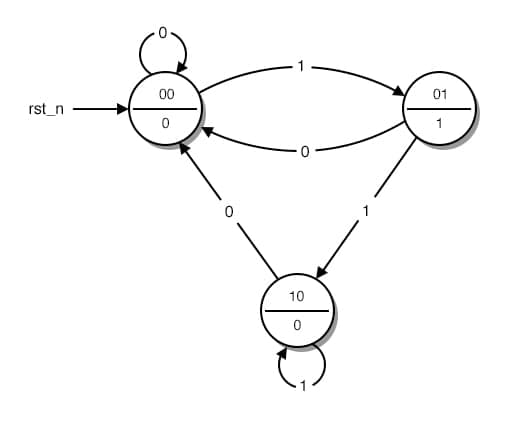

After all, in its basic form, a finite state machine is just a machine (“entity”) that:

Can only be an certain (“finite”) states

Defines the transitions among those states

Defines the side effects running on those transitions

The logic of those states (what they are, what are the possible transitions, which events trigger them, what side effects they trigger…) is defined in the machine config itself. The actor is “just” the runner that we can subscribe to.

The only method that is a bit complex there is the “send” method, used to interact with the machine, sending events via the actor, informing the machine of “changes” in the outside world so it can do its thing, without us having to do them imperatively.

So, back to the actor:

The send method looks like this:

send = (event: TEvent): void => {

if (this.snapshot.status !== "active") {

if (process.env.NODE_ENV === "development") {

console.warn(

`Event "${event.type}" was sent to stopped actor "${this.id}"`,

)

}

return

}

try {

// Get next state and actions (pure computation)

const result: TransitionResult<TContext, StateValue> =

this.machine.transition(this.snapshot, event)

// Execute actions and update context

const newContext = this.executeActions(

result.actions,

event,

)

// Invalidate cache before updating snapshot

this.lastSnapshot = null

// Update snapshot

const nextSnapshot: Snapshot<TContext, StateValue> = {

status: this.snapshot.status,

value: result.value,

context: newContext,

}

// Update state and notify

this.snapshot = nextSnapshot

this.notify()

} catch (error) {

this.handleError(error)

}

}Take a look at that again: the actor just receives the configuration from the machine, get’s from it which transitions are expected and then executes the actions and update the context accordingly, reaching a new state until it receives a new even from the actor user, repeating the process until the state reach is a final step or the actor is manually stopped.

In that sense, the actor is just a “runner”. The logic is in the machine, and the actor is just our way to interact with the machine through events via the send method.

The machine

Let’s move now to the meat… the state machine.

Before moving to the state machine, is worth remember the main idea: we are just trying to define a system that…

…has a finite number of states

…can handle transitions between those states (is it a possible transition? is it protected by a guard?…)

…can trigger side effects in certain transitions or phases (on entry, on exit,…)

The first thing we need to be able to make it work is a way to describe our state machine.

For that, JSON seems a good choice for several reaons:

It’s what xstate uses, which means: it’s probably a good idea moving forward, and we can use some of the xState tools for free (like the visualizer - to a certain point).

It’s obiquitous in web development

It’s Ai ready. AI development is here to stay. Json is easily understood by most of the llm providers. You’d be surprised how far llms can take you with a clear api to create state machines.

It’s Serializable, that is, can be sent thorugh the network, saved in a database, etc.

The last one could seem irrelevant, and it’s in this phase of the library, but in the future it will allow us to persist state machine configurations.

The Machine Config

The configuration object of our finite state machine is quite big, and can get a bit complex. Instead of trying to digest all at once, let’s take a look at it’s API from a “big picture perspective”:

export type StateValue = string;

export type EventObject = { type: string; [key: string]: any };

export type MachineContext = Record<string, any>;

export interface MachineConfig<TContext, TEvent extends EventObject> {

id: string;

initial: StateValue;

context: TContext;

on?: {

[K in TEvent['type']]?: TransitionConfig<TContext, TEvent>;

};

states: {

[key: string]: StateNodeConfig<TContext, TEvent>;

};

}Hopefully, the code above is more or less self explanatory:

id: Needed for debugging when we are running several machines in parallel. Indeed, in future versions I should add a way to differentiate between different instances of the same machine configuration, something that I did not foresee when creating the library and that seems pretty obvious.

initial: The initial state of the machine, which, as you can see, is just a string. I wrapped it in a custom type to help with type inference.

context: Data we keep within the machine (see below explanation)

on: The “on” key always points to transitions configurations (we will see those later). When the “on” key is at the machine configuration level (instead of inside a specific state), is defining transitions that will be available at any given state. Think for example of a “RESET” event: regarless of the state of the machine, we may want to act on it, reseting the machine. Instead of adding that transition to all states, we add it at the machine config level.

states: the different state of the machine (keys) and their configuration (values).

So, the first part of our machine config could look like this:

{

id: 'onboarding',

initial: 'generatingPost',

context: INITIAL_CONTEXT,

on: {

GO_TO_GENERATING_POST: //...,

RESET: // ...,

SET_USER_ID: // ...,

// states

};So, we are saying:

“My machine name is onboarding which start in the state generatingPost, with this initial data (which is probably empty) and these are the events that should be manage regarless on which state we are in”

Regarding “context”:

Context is a pragmatic design choice. Pure FSMs require explicitly modeling every possible state, but for practical applications like form inputs, this would mean creating a state for every possible string value—clearly impractical. Instead, we use context to store dynamic data while keeping our state space finite. The key insight: we simplify 'infinite' states (like all possible input values) into meaningful semantic states (like 'clean' vs 'dirty'), and store the actual data in context.

Think for example about one of the simplest examples of finite state machines: an input field. If we defined the states of the input, they would be something like this:

clean: aka, the field was not modified

dirty: aka, has some text on it

But “has some text on it” is actually a “bucket state” for a veeeeery high number of potential states: as many as string combinations can be written in the input field.

Creating a finite state machine configuration with all those states would be an impossible (and useless) task, so instead of trying that, we simplified all those states on a unique state: “dirty”. In order to not lose information, we store the string of the input in the context.

That simplifies the number of states needed, makes it possible for us to work with finite state machines, and should not introduce problems in our transition configs and the behaviour of our machine if it’s properly used.

Let’s now unwrap the TransitionConfig, which will help us then do the same with the StateNodeConfig

export interface TransitionConfig<

TContext extends MachineContext,

TEvent extends EventObject

> {

target?: StateValue;

guards?: Guard<TContext, TEvent>[];

actions?: Action<TContext, TEvent>[];

}target: The state where the machine will end If the transition can happen and it’s successful.

guards: Conditions that have to be met for the transition to be able to proceed. We could also call this “blockers”.

actions: side effects that will happen in the transition from the current state to the target state. Only executed if the transitions is actually performed (it’s not blocked by guards).

Guards are just functions which, given the context and the event received, should return a boolean to flag whether the transition can be performed or not:

export interface Guard<

TContext extends MachineContext,

TEvent extends EventObject

> {

type: string;

condition: (context: TContext, event: TEvent) => boolean;

}While actions look like this:

export interface ActionArgs<

TContext extends MachineContext,

TEvent extends EventObject

> {

context: TContext;

event: TEvent;

self: ActorRef<TContext, TEvent>;

}

export interface Action<

TContext extends MachineContext,

TEvent extends EventObject

> {

type: string;

exec: (args: ActionArgs<TContext, TEvent>) => void | Record<string, any>;

}There is one special action that deserves mentioning: changing the context. One of the principles that makes our system so reliable is the fact that the context cannot be changed from the outside: every change to the state machine state or context is a consequence of the current state of the machine plus certain event. In order to be able to modify the context then, we define the assign action:

// actions.ts

export function assign<

TContext extends MachineContext,

TEvent extends EventObject

>(

assignment: (context: TContext, event: TEvent) => Partial<TContext>

): Action<TContext, TEvent> {

return {

type: 'xstate.assign',

exec: ({ context, event }: ActionArgs<TContext, TEvent>) => {

return assignment(context, event);

},

};

}What makes that action special is that the returned object is then merged into the context in the send method implementation (within the executeAction helper):

private executeActions(

actions: ActionExecutor<TContext, TEvent>[],

event: TEvent

): TContext {

let context = { ...this.snapshot.context };

actions.forEach((action) => {

// assign actions updates the context

if (action.type === 'xstate.assign') {

const updates = action.exec({

context,

event,

self: this,

});

context = { ...context, ...updates };

} else {

// other actions just execute

action.exec({ context, event, self: this });

}

});

return context;

}So, we are now able to define:

The initial state of our machine

The transitions that are possible in any state

Guards for those transitions

What remains is one of the core parts of the config: the StateNodeConfig.

For every state in our machine, we define a config that looks like this:

export interface StateNodeConfig<TContext, TEvent extends EventObject> {

on?: {

[K in TEvent['type']]?: TransitionConfig<TContext, TEvent>;

};

entry?: Action<TContext, TEvent>[];

exit?: Action<TContext, TEvent>[];

}Entry and exit are quite self explanatory: they are the actions that will be performed when the state machine enters (exits) the given state.

The “on” object contains the transitions for the different events that this state should handle. We already saw the TransitionConfig when we defined those at the machine configuration level.

And with that, we are done defining the config of our state machine.

So… so far we have:

An actor that is able to run the logic of our machine

The machine config that defines the different states and transitions of our machine

What remains is the logic of the transitions, the interpreter of the confi object that we just created. And, believe it or not - it’s quite simple. So simple that I am gonna copy pasting it right here, and - instead of explaining the code in a paragraph, let’s go through it line by line:

export class StateMachine<

TContext extends MachineContext,

TEvent extends EventObject

> {

readonly config: MachineConfig<TContext, TEvent>;

constructor(config: MachineConfig<TContext, TEvent>) {

this.config = config;

}

// Nothing too fancy: given a state and the received event, return the transition config...

getTransition(state: StateValue, event: TEvent) {

const stateNode = this.config.states[state];

return (

// ... of that given state

stateNode?.on?.[event.type as keyof typeof stateNode.on] ||

// ...or the global transition if the given state does not handle that event

this.config.on?.[event.type as keyof typeof this.config.on]

);

}

// Given a state, an event and the current context, can we proceed with a transition?

can(state: StateValue, event: TEvent, context: TContext): boolean {

const transition = this.getTransition(state, event);

// If the transition does not exist, no, we cannot proceed

if (!transition) return false;

// If it exists...

return (

// if there are guards, return the result of the guard...

transition.guards?.every((guard) => guard.condition(context, event)) ??

// ... if there are no guards, we can proceed

true

);

}

getInitialSnapshot(): Snapshot<TContext, StateValue> {

return {

status: 'active',

context: { ...this.config.context } as TContext,

value: this.config.initial,

};

}

// This is the core of the class: the transition logic that interprets the config

// Given the current snapshot (state of the machine and context) and the received event,

// return the target state and the actions to be performed by the runner / actor.

transition(

snapshot: Snapshot<TContext, StateValue>,

event: TEvent

): TransitionResult<TContext, StateValue> {

const currentState = snapshot.value;

const transition = this.getTransition(currentState, event);

// The !transition check is redundant, to be fix in the next release

if (!transition || !this.can(currentState, event, snapshot.context)) {

return {

value: currentState,

actions: [],

};

}

// Collect the actions for the transition (which would be the exit actions of the current state,

// the entry actions of the target state, and the actions of the transition itself (more on this later)

// Exit current state → Execute transition actions → Enter new state

const targetState = transition.target || currentState;

const actions: ActionExecutor<TContext, TEvent>[] = [];

// Collect exit actions

if (targetState !== currentState) {

const currentStateNode = this.config.states[currentState];

if (currentStateNode?.exit) {

const exitActions = Array.isArray(currentStateNode.exit)

? currentStateNode.exit

: [currentStateNode.exit];

actions.push(...exitActions);

}

}

// Collect transition actions

if (transition.actions) {

const transitionActions = Array.isArray(transition.actions)

? transition.actions

: [transition.actions];

actions.push(...transitionActions);

}

// Collect entry actions

if (targetState !== currentState) {

const targetStateNode = this.config.states[targetState];

if (targetStateNode?.entry) {

const entryActions = Array.isArray(targetStateNode.entry)

? targetStateNode.entry

: [targetStateNode.entry];

actions.push(...entryActions);

}

}

return {

value: targetState,

actions,

};

}

}

Why do we have “state actions” (entry and exit actions) and “transition actions”?

Well, some actions are inherently linked to a given state, regardless of “how we reach that state”. We should not then need to add that action to every transition that leads to that state, but to the state itself. That’s what entry actions are for.

For example, if we are creating a machine that handles a video player, we could have a playing state that looks like this:

states: {

playing: {

entry: ['requestWakeLock', 'hideControls', 'trackPlaybackStart'],

exit: ['releaseWakeLock', 'showControls', 'trackPlaybackEnd'],

// ... transitions

}

}Regardless of how we reach the playing state, those actions need to be performed on entry and on exit.

On the other hand, some actions are necesarily related to a “change” in the state of our machine, and not to the state itself. Those actions should be “transition actions”.

For example, a form submission transition config could look like this:

on: {

SUBMIT: {

target: 'success',

actions: ['validateForm', 'saveToDatabase', 'sendConfirmationEmail'],

guards: ['isFormValid']

}

}The actions happen as a consequence of the machine receiving the SUBMIT event and the form being valid (via the guard).

And that’s all about my first library, tiny-machine.

It’s by no means perfect, it’s a first version and a very simple one, but it does the job for my needs and hopefully you could use it as an introduction to the idea of finite state machines. If you want to add something, suggest a change, or just make a correction (my apologies in advance), feel free to shoot me an email at ricardo@rimakes.com.

In the next update, I will polish the post and add some example of how to use it.